An Introduction to Growth Mixture Models with brms and easystats

The easystats team

2026-02-17

Source:vignettes/practical_growthmixture.Rmd

practical_growthmixture.RmdIntroduction

Growth Mixture Models (GMMs) are a powerful statistical technique used to identify unobserved subgroups (latent classes) within a population that exhibit different developmental trajectories over time. They are a subclass of latent class analysis and are particularly useful in longitudinal research to understand heterogeneity in how individuals change.

This vignette demonstrates how to conduct a Growth Mixture Model

using the brms package for Bayesian modeling and the

easystats ecosystem (particularly modelbased,

parameters, and see) for easy interpretation

and visualization.

Loading Packages and Data

First, we load the necessary packages. brms is for model

fitting, and easystats is a suite of packages that

simplifies the entire process of statistical analysis and

visualization.

The Dataset

We will use the qol_cancer dataset, which is included in

the datawizard package. This dataset contains longitudinal

data on the health-related quality of life (QoL) of cancer patients,

measured at three time points: pre-surgery, and 6 and 12 months

post-surgery.

The dataset includes the following variables:

-

ID: A unique identifier for each patient. -

QoL: The outcome variable, a Quality of Life score. -

time: The measurement time point (1 = pre-surgery, 2 = 6 months, 3 = 12 months). -

hospital: The hospital where the operation was performed. -

education: The patient’s education level (low, mid, high). -

age: The patient’s age (standardized).

Let’s prepare the data by converting the time and

hospital variables to factors.

Fitting the Growth Mixture Model

The core of a GMM in brms is the mixture()

family, which allows us to model the outcome variable as a mixture of

distributions. In our case, we hypothesize that there are distinct

subgroups of patients with different QoL trajectories. We will fit a

model with two latent classes (nmix = 2).

The model formula

QoL ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID)

specifies that QoL is predicted by several fixed effects

(time, hospital, etc.) and a random effects

structure (1 + time | ID). This random effects part is

crucial for growth models, as it allows each patient (ID)

to have their own baseline QoL (random intercept 1) and

their own rate of change over time (random slope time).

Running the Model

Fitting a Bayesian mixture model can be computationally intensive.

For the purposes of this vignette, we will download a pre-fitted model

from the easystats repository.

# Download the pre-fitted model

brms_mixture_2 <- download_model("brms_mixture_2")If you wish to fit the model yourself, you can use the following code. Be aware that it may take several minutes to run.

# In case of convergence issues, specifying priors can help. The priors are

# set for the population-level intercept of each mixture component (mu1, mu2).

# prior <- c(

# prior(normal(0, 10), class = Intercept, dpar = mu1),

# prior(normal(0, 10), class = Intercept, dpar = mu2)

# )

set.seed(1234)

brms_mixture_2 <- brms::brm(

formula = QoL ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID),

data = qol_cancer,

family = mixture(gaussian, nmix = 2), # Gaussian mixture with 2 classes

chains = 4, # Number of MCMC chains

iter = 2000, # Total iterations per chain

cores = 4, # Use 4 CPU cores

seed = 1234, # For reproducibility

silent = 2, # Suppress Stan progress

refresh = 0

)You can use different factors to predict the outcome for each group in your data. To do this, simply create a separate prediction formula for each part of your model. For instance, you could use one set of factors to predict the quality of life for “Group 1” and a different set for “Group 2”. You can even use factors to predict which group someone is likely to belong to. While this guide won’t cover the details, a code example at the end shows you how.

Interpreting the Model

With our model fitted, we can now use the easystats

functions to understand the results.

Predicted Class Membership

Our first step is to determine which latent class each patient

belongs to at each time point. We can use the

estimate_prediction() function from the

modelbased package with

predict = "classification".

out <- estimate_prediction(brms_mixture_2, predict = "classification")

head(out)

#> Model-based Predictions

#>

#> time | hospital | education | age | ID | Predicted | Probability

#> ------------------------------------------------------------------

#> 3 | 1 | mid | -3.60 | 1 | 1 | 0.72

#> 1 | 1 | mid | -3.60 | 1 | 2 | 0.51

#> 2 | 1 | mid | -3.60 | 1 | 1 | 0.50

#> 1 | 1 | mid | 1.40 | 10 | 2 | 0.97

#> 2 | 1 | mid | 1.40 | 10 | 2 | 0.97

#> 3 | 1 | mid | 1.40 | 10 | 2 | 0.97

#>

#> time | 95% CI | Residuals

#> -------------------------------

#> 3 | [0.00, 1.00] | 40.67

#> 1 | [0.00, 1.00] | 39.67

#> 2 | [0.00, 1.00] | 32.33

#> 1 | [0.86, 1.00] | 81.33

#> 2 | [0.85, 1.00] | 81.33

#> 3 | [0.89, 1.00] | 81.33

#>

#> Variable predicted: QoL

#> Predictions are on the classification-scale.The output table shows the Predicted class for each

observation, along with the Probability of that

classification. Now, let’s join these predicted classes back to our

original dataset for visualization.

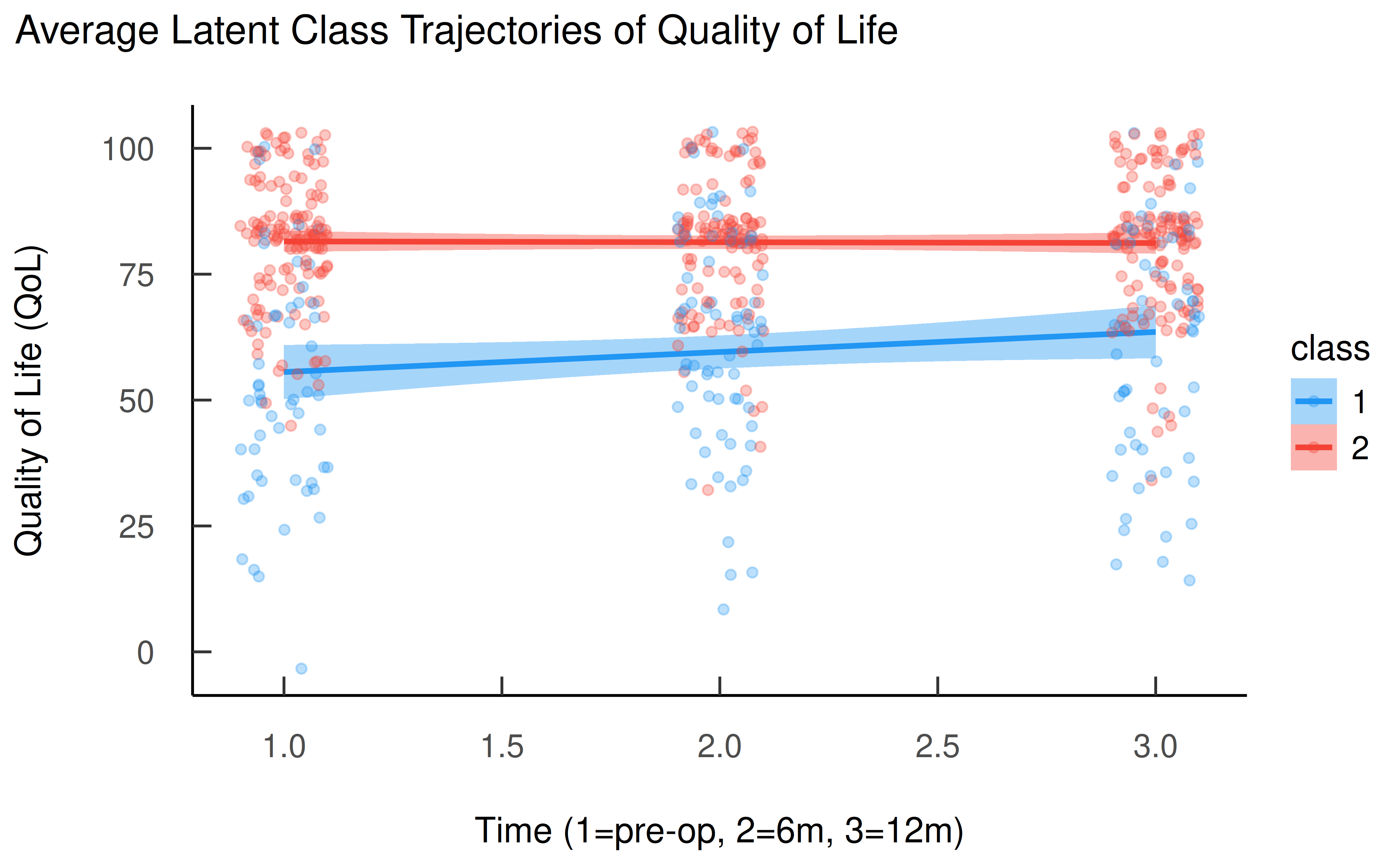

Visualizing Latent Class Trajectories

Now we can visualize the average QoL trajectories for each latent class. This is the most intuitive way to understand the results of a GMM.

ggplot(d, aes(x = as.numeric(time), y = QoL, color = class, fill = class)) +

geom_smooth(method = "lm") +

geom_point(alpha = 0.3, position = position_jitter(width = 0.1)) +

labs(

title = "Average Latent Class Trajectories of Quality of Life",

x = "Time (1=pre-op, 2=6m, 3=12m)",

y = "Quality of Life (QoL)"

) +

theme_modern(show.ticks = TRUE) +

scale_color_material() +

scale_fill_material()

The plot clearly reveals two distinct groups:

- Class 1 (blue): This group starts with a lower Quality of Life, but shows a steady improvement over the 12-month period.

- Class 2 (red): This group starts with a much higher Quality of Life and maintains this high level throughout the observation period.

Inspecting Model Parameters

To understand what predicts the outcome within each class, we can

inspect the model parameters using model_parameters() from

the parameters package.

model_parameters(brms_mixture_2, diagnostic = NULL, drop = "time")

#> # Class 1

#>

#> Parameter | Median | 95% CI | pd

#> -------------------------------------------------

#> (Intercept) | 48.16 | [ 18.63, 63.83] | 99.70%

#> hospital1 | 3.82 | [-17.62, 19.56] | 56.20%

#> educationmid | 9.32 | [ 3.04, 24.36] | 98.65%

#> educationhigh | 13.04 | [ -3.75, 24.99] | 94.10%

#> age | 0.48 | [ -0.83, 1.20] | 84.00%

#>

#> # Class 2

#>

#> Parameter | Median | 95% CI | pd

#> -------------------------------------------------

#> (Intercept) | 75.51 | [ 63.81, 81.50] | 100%

#> hospital1 | -1.29 | [-10.41, 8.28] | 56.70%

#> educationmid | 3.98 | [ 0.14, 10.17] | 97.65%

#> educationhigh | 11.53 | [ 5.79, 19.47] | 100%

#> age | -0.37 | [ -0.65, 0.29] | 86.25%The output is neatly separated by class. We can see, for example,

that higher education (educationmid,

educationhigh) is associated with a higher QoL in both

classes, but the magnitude of the effect differs.

Estimated Marginal Means

We can dive deeper by estimating the marginal means of

QoL for different predictor levels within each class. Let’s

look at the effect of education. The

predict = "link" argument is essential for mixture models,

as it computes the means for each class separately.

estimate_means(brms_mixture_2, by = "education", predict = "link")

#> Average Predictions

#>

#> education | Median (CI) | pd | Class

#> -----------------------------------------------

#> low | 57.06 (38.01, 59.73) | 100% | 1

#> low | 73.48 (70.12, 78.09) | 100% | 2

#> mid | 67.48 (52.25, 69.19) | 100% | 1

#> mid | 79.19 (75.50, 81.05) | 100% | 2

#> high | 68.89 (46.29, 74.84) | 100% | 1

#> high | 85.52 (82.70, 86.94) | 100% | 2

#>

#> Variable predicted: QoL

#> Predictors modulated: education

#> Predictions are on the link-scale.This table gives us the expected mean QoL for each

education level, conditional on class membership. For instance, a

patient with “low” education in Class 2 has an estimated mean QoL of

74.43, whereas a similar patient in Class 1 has an

estimated mean QoL of 53.92.

Comparing Levels with Contrasts

We can also compute contrasts between predictor levels to understand the magnitude of differences.

If we compute contrasts without predict = "link",

estimate_contrasts() averages the effects across both

classes, giving a general sense of inequality.

estimate_contrasts(

brms_mixture_2,

contrast = "education"

)

#> Averaged Contrasts Analysis

#>

#> Level1 | Level2 | Median (CI) | pd

#> ----------------------------------------------

#> mid | low | 7.26 (4.85, 10.05) | 100%

#> high | low | 12.73 (9.31, 14.99) | 100%

#> high | mid | 5.01 (2.22, 7.02) | 99.95%

#>

#> Variable predicted: QoL

#> Predictors contrasted: education

#> Contrasts are on the response-scale.More interestingly, we can set predict = "link" to get

contrasts both within and between classes. This

provides a very detailed picture.

estimate_contrasts(

brms_mixture_2,

contrast = "education",

predict = "link"

)

#> Averaged Contrasts Analysis

#>

#> Level1 | Level2 | Median (CI) | pd

#> ------------------------------------------------

#> 1 mid | 1 low | 11.53 ( 3.15, 23.66) | 98.75%

#> 1 high | 1 low | 15.02 ( 0.73, 23.60) | 98.00%

#> 2 low | 1 low | 20.95 ( 12.17, 34.64) | 100%

#> 2 mid | 1 low | 23.95 ( 18.32, 39.03) | 100%

#> 2 high | 1 low | 29.84 ( 25.77, 45.80) | 100%

#> 1 high | 1 mid | 2.62 (-12.90, 8.16) | 69.80%

#> 2 low | 1 mid | 9.38 ( 2.59, 19.67) | 99.95%

#> 2 mid | 1 mid | 12.39 ( 8.73, 25.17) | 100%

#> 2 high | 1 mid | 18.27 ( 16.16, 31.48) | 100%

#> 2 low | 1 high | 4.00 ( 1.23, 24.70) | 99.55%

#> 2 mid | 1 high | 10.21 ( 6.19, 30.21) | 100%

#> 2 high | 1 high | 16.68 ( 12.08, 37.17) | 100%

#> 2 mid | 2 low | 5.78 ( 2.78, 7.47) | 99.90%

#> 2 high | 2 low | 11.73 ( 8.50, 14.03) | 100%

#> 2 high | 2 mid | 5.90 ( 4.29, 8.18) | 100%

#>

#> Variable predicted: QoL

#> Predictors contrasted: education

#> Contrasts are on the link-scale.The output is rich with information. For example,

2 high | 2 low shows the contrast between high and low

education within Class 2 (an increase of 11.53 in

QoL), while 2 low | 1 low compares a patient with low

education in Class 2 to a patient with low education in Class 1 (a

difference of 19.34).

Quantifying Inequality

Finally, estimate_contrasts() has a powerful

comparison = "inequality" argument. This calculates the

average absolute difference between all levels of a predictor, providing

a single number that quantifies the overall disparity associated with

that variable. Let’s compare the inequality associated with

education versus hospital.

estimate_contrasts(

brms_mixture_2,

contrast = c("education", "hospital"),

comparison = "inequality"

)

#> Averaged Inequality Analysis

#>

#> Parameter | Median (CI) | pd

#> -------------------------------------

#> education | 8.46 (4.85, 11.42) | 100%

#> hospital | 1.40 (0.11, 8.87) | 100%

#>

#> Variable predicted: QoL

#> Predictors contrasted: education, hospital

#> Differences are on the response-scale.The results are striking. The inequality median for

education is 8.46, while for

hospital it is only 1.40. This suggests that a

patient’s education level is associated with far greater disparities in

their quality of life trajectory than the hospital where they received

treatment.

Conclusion

Growth Mixture Models are an excellent tool for uncovering hidden

heterogeneity in longitudinal data. By using brms to fit

these complex models and the easystats ecosystem to process

and interpret them, researchers can move from complex output to

actionable insights with ease. This vignette has shown how to identify

latent classes, visualize their trajectories, and quantify the effects

of covariates in a straightforward and intuitive workflow.

Supplement

The estimation of latent class membership in finite mixture models

within the R package brms is not governed by a single,

fixed mechanism. Instead, brms provides a flexible and

powerful framework that allows the researcher to explicitly define the

data-generating process, including the factors that determine class

membership. The central question of whether class membership is

determined by the outcome’s trajectory, by predictors, or if predictors

are only relevant after classification, can be addressed directly: all

of these scenarios represent valid modeling choices that can be

implemented within brms. In a mixture model, the

probabilities of belonging to each latent class - the mixing

proportions, denoted as \theta - are

themselves parameters of the model. Consequently, they can be modeled as

a function of predictors.

Here’s a summary of how to specify these different scenarios in

brms:

| Scenario | Research Question | Example brms Formula |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Mixture | “Are there two or more distinct latent groups in my outcome data, ignoring all predictors?” | bf(y ~ 1, family = mixture(gaussian, nmix = 2)) |

| Predicting Component Means | “Does a treatment (x) affect the outcome

differently for the two latent groups?” |

bf(y ~ 1, mu1 ~ x, mu2 ~ x, family = mix)

or simply bf(y ~ x, family = mix)

|

| Predicting Mixing Proportion | “Does a demographic variable (z) predict

which latent group an individual is likely to belong to?” |

bf(y ~ 1, theta2 ~ z, family = mix) |

| Full Distributional Model | “How do treatment (x) and demographics

(z) jointly influence both the outcome within each group

and the probability of group membership?” |

bf(y ~ 1, mu1 ~ x, mu2 ~ x, theta2 ~ z, sigma ~ group, family = mix) |

Example Codes

# this model is actually equivalent to the one we used in the vignette

# but it allows for different predictors for each class

brms::brm(

bf(

# formula for individual trajectories

QoL ~ 1 + (1 + time | ID),

# predictors for class 1

mu1 ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID),

# predictors for class 2

mu2 ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID),

family = mixture(gaussian, nmix = 2)

),

data = qol_cancer,

chains = 4, # Number of MCMC chains

iter = 1000, # Total iterations per chain

cores = 4, # Use 4 CPU cores

seed = 1234, # For reproducibility

refresh = 0

)

# in this example, we also model the class membership probabilities

brms::brm(

bf(

# formula for individual trajectories

QoL ~ 1 + (1 + time | ID),

# predictors for class 1

mu1 ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID),

# predictors for class 2

mu2 ~ time + hospital + education + age + (1 + time | ID),

# predictors for class membership probabilities

theta1 ~ hospital + education,

theta2 ~ hospital + education + age,

family = mixture(gaussian, nmix = 2)

),

data = qol_cancer,

chains = 4, # Number of MCMC chains

iter = 1000, # Total iterations per chain

cores = 4, # Use 4 CPU cores

seed = 1234, # For reproducibility

refresh = 0

)